Entrepreneurial Conservation Through Rock Climbing

I first published a version of this article Entrepreneurial Conservation through Rock Climbing on Raxa Collective, when I was operating my hotel, La Buena Onda, in Matagalpa, Nicaragua in 2012.

The burgeoning sport of rock climbing is an excellent example of how an adventure sport can propagate the conservation of natural areas through private sector initiatives. In the early days of the sport, climbers would hammer iron “pitons” into cracks in the rock as they ascended, and attach ropes to them in order to protect against falls. The pitons were not designed to be removed, and can still be seen on some of the classic climbs around the world. Visionary thinkers such as Yvon Chouinard (of the Patagonia clothing and gear company) were unsatisfied with the fact that with each new climb, permanent scars were left in the rock, and set out to devise other means of protection. Nowadays, climbers use removable “nuts” and “cams” that still protect against falls, but leave no trace in the rock. In fact, rock climbers have even set up organizations such as the Access Fund that participate in conservation and land protection initiatives. The sport has also helped to bring much needed revenue to rural areas as diverse as Slade Kentucky, Yangshuo, China, or Cuenca, Ecuador.

I was an avid rock climber before moving to Nicaragua. Unfortunately, rock climbing had not yet arrived to the country making it virtually impossible to find gear or fellow climbers to scout out new rocks. On top of that, any promising looking cliffs were either covered in tropical vegetation or too brittle to climb. After about 3 years of keeping my eyes peeled on bus rides for rock outcroppings, and unsuccessful exploratory hikes through countless coffee farms did I finally found some astounding, climbable rock.

The Somoto Canyon is 3 hours north of the capital city of Managua, and about 1.5 hours from my hotel in Matagalpa. We packed up our climbing equipment and some friends and set out to explore.

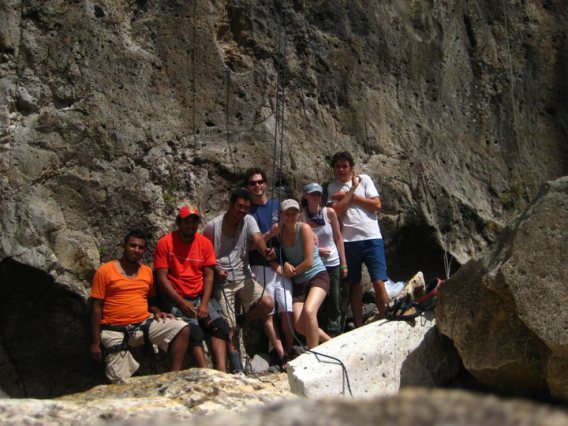

What we found was amazing. 100-meter sheer, solid cliffs rise up from a deep, narrow river. The rock is ideal for climbing. We met some local tour guides and discovered that they had been rappelling here for years, but did not have the equipment or knowledge to start climbing. They had read about the sport and were eager to learn for themselves.

We set up an anchor station at the top of a cliff, and climbed what we think are some of the first routes in the country. After a full day of climbing and swimming, we set camp on a sandy beach inside the canyon and spent the night.

The canyon has been attracting some tourist attention over the past few years, but our guides told us that they would love to be able to offer climbing tours, and thought it could help attract much needed tourist dollars to the area. I agreed to help Gonzalo (the owner of Namancambre Tours) promote his tour company in my hotel in Matagalpa, and we decided to meet again soon.

After telling a few climbing friends back in the states about our experience, they generously assembled together a huge package of donated equipment such as climbing shoes, harnesses, ropes and carabineers.

My fiancée (now wife and co-founder of Firelight Camps, Emma Frisch) and I returned to Somoto and spent a day teaching the guides the proper way to use the equipment. Gonzalo, Luis and Chepe were overjoyed with the new gear, and we were happy to see them replace their very old and rusty harnesses.

Tourists can now climb a few select areas of the canyon with Gonzalo and his tour guides. We are working to develop the canyon in a safe and sustainable way, and hope to attract more climbers to the area in the future. More climbers means economic development for Somoto. Responsible tour guides like Gonzalo can ensure that the canyon is used in an environmentally sustainable way, and the presence of appreciative tourists means it will be harder for illegal dumping or vandalism to happen here.